Some of the photographs displayed here were found in a plastic recipe box in the trunk of an abandoned Plymouth, along with a rusty German Luger and some medals from both world wars, at the Plank Road Auto Wreckers on the outskirts of Sarnia, Ontario, in 1995. The car was being stripped and sold for parts. When the recipe box was opened, the owner’s wife recognized my uncle Mark in one of the photographs and called him up. The pictures had been taken by my father and developed at Woolworth’s in the late 1970s and early ’80s. The medals and the Luger had belonged to my great-grandfather, Eric. W. Harris.

Uncle Mark passed the photos over to me in 2001, at the Sarnia train station. That afternoon I learned that my father had lived in his two-tone Plymouth for many months at a time during the 1990s.

My father is schizophrenic. When I lived in Sarnia, I used to see him walking in the early morning, carrying a hockey bag full of refundable glass bottles he’d found near Sarnia Bay. We never spoke. He does not believe that I have aged since the time of his divorce from my mother in 1981. In the alternative universe of these photos, I am eternally nine years old.

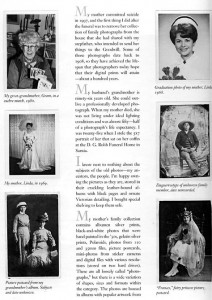

My mother committed suicide in 1997, and the first thing I did after the funeral was to remove her collection of family photographs from the house that she had shared with my stepfather, who intended to send her things to the Goodwill. Some of these photographs date back to 1908, so they have achieved the lifespan that photographers today hope that their digital prints will attain — about a hundred years.

My husband’s grandmother is ninety-six years old. She could out-live a professionally developed photograph. When my mother died, she was not living under ideal lighting conditions and was almost fifty — half of a photograph’s life expectancy. I was twenty-five when I stole the 5×7 portrait of her that sat on her coffin at the D. G. Robb Funeral Home in Sarnia.

I know next to nothing about the subjects of the old photos — my ancestors, the people. I’m happy owning the pictures as they are, stored in their crackling leather-bound albums with black pages and ornate Victorian detailing. I bought special shelving to keep them safe.

My mother’s family collection contains albumen silver prints, black-and-white photos that were hand painted in the ’50s, gelatin silver prints, Polaroids, photos from 110 and 35mm film, picture postcards, mini-photos from sticker cameras and digital files with various resolutions (stored on two hard drives). These are all loosely called “photographs,” but there is a wide variation of shapes, sizes and formats within the category. The photos are housed in albums with popular artwork from their eras. They tell stories about the personality, taste and economic status of each family archivist. Sometimes notes have been left beside a photo. How can I re-archive the photos without losing the context? Will I have time left for the present if I dedicate myself to the huge task of preserving the past?

If I don’t do something with the photos, they will degrade, and maybe someday my two babies will have babies who will be upset with Grandma Sharon for neglecting 150 years of their heritage. Or maybe they won’t care.

I hope I raise my sons so that they care, but not too much. My older son is seven and he loves looking at his epic-length baby books (of which there are three). He wants a digital camera for his birthday. My younger son, Cyan, is named after a colour in CMYK printing, and is learning proper nouns while looking at snapshots of places and people he has visited.

These days, when distant family members die, I receive envelopes of their photos. Usually the pictures are not labeled and I can’t identify the subjects. I recently contacted a third cousin I’ve never met to ask if she has photos of my grandfather, who was killed in an accident before I was born. When I attend biannual family gatherings four hours from my home, I am the family member most likely to take photos and send them to everyone else. My grandparents, who winter in Florida every year, watch their grandchildren grow up through school portraits and snapshots in holiday cards. Now it’s easy to make personal, functional gifts — calendars, coffee mugs, mouse pads, even hockey pucks — with family images.

As far as I know, our family doesn’t have real estate, jewels, numbered bank accounts or even great wisdom to bequeath to younger generations. But it can be said that we took a lot of photographs.

At this point in my life (33 percent of the expected lifespan of a photograph), I don’t have parents, but I have shelves of their images. I know the photographs of my family of origin more intimately than I know the people in them.

Photographs in a plastic recipe box are more familiar than family.